Curious lessons I learned from Banned Books Week

September 27, 2016

Marketing and Communications Coordinator*VISTA

What happens to all the books that are banned to languish in dusty boxes and dark closets, never to be opened or to transport a child to otherworldly dimensions? And what happens to us, when we exile literary universes? Banned Books Week celebrates the notion that all literature is valuable, that it functions in some way for someone, somewhere. It’s a week of lionizing the written word, even when those words can be unfamiliar, controversial, or disquieting.

Neil Gaiman, the popular English author of works with a fantasy, sci-fi, or otherworldly element, developed an essay titled “Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading and Daydreaming” around the importance of reading, the freedom supplied by libraries, and the usefulness of fiction in daydreaming. In his essay he comments on censorship:

“Every now and again it becomes fashionable among some adults to point at a subset of children’s books, a genre, perhaps, or an author, and to declare them bad books, books that children should be stopped from reading […] There are no bad authors for children, that children like and want to read and seek out, because every child is different. They can find the stories they need to, and they bring themselves to stories. A hackneyed, worn-out idea isn’t hackneyed and worn out to someone encountering it for the first time. You don’t discourage children from reading because you feel they are reading the wrong thing. Fiction you do not like is the gateway drug to other books you may prefer them to read. And not everyone has the same taste as you.”

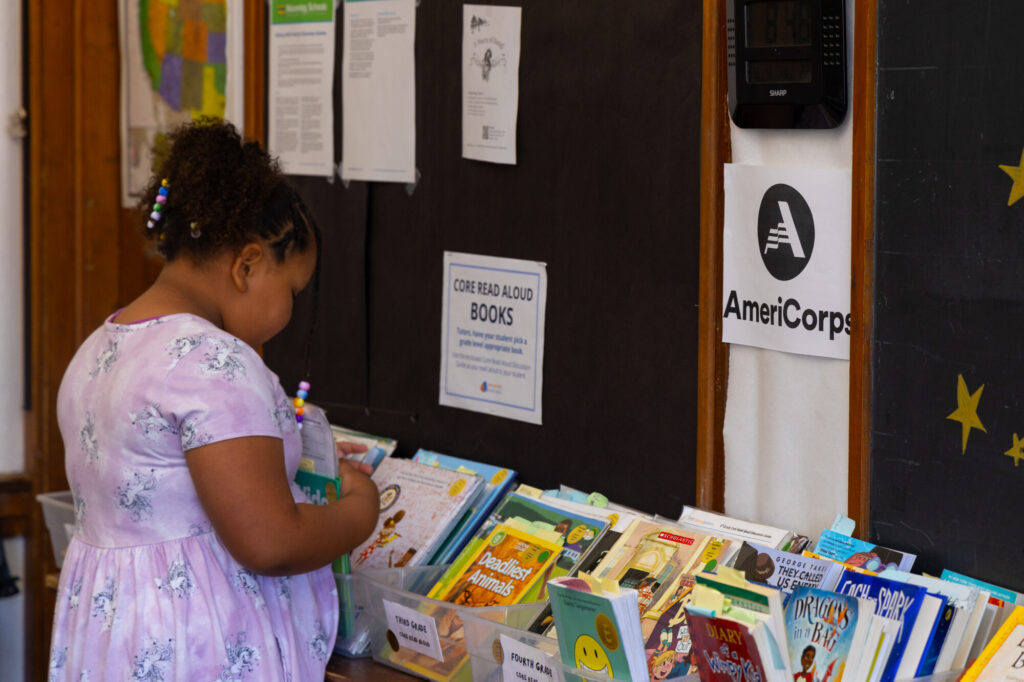

Gaiman points to the associative nature of reading and the many positive characteristics any reading can impart. That actually echoes an important element of Reading Partners’ approach: to allow kids some choices in what they read and to discover joy based on who they are and what interests them.

The motives for book banning can be ideological, religious, and even political.The reasons given often seem surprising and even hilarious to us now, standing where we are looking back at history. It’s hard to keep a straight face recalling that The Wizard of Oz was banned for “bringing children’s minds to a cowardly level.” Or that in 1987 The American Heritage Dictionary was banned for its “objectionable entries.” Gaiman comments that:

“Well-meaning adults can easily destroy a child’s love of reading: stop them reading what they enjoy, or give them worthy-but-dull books that you like, the twenty- first-century equivalents of Victorian “improving” literature. You’ll wind up with a generation convinced that reading is uncool and, worse, unpleasant […] Fiction can show you a different world. It can take you somewhere you’ve never been. Once you’ve visited other worlds, like those who ate fairy fruit, you can never be entirely content with the world that you grew up in. And discontent is a good thing: people can modify and improve their worlds, leave them better, leave them different, if they’re discontented.”

I’m a fan of learning from the past. By keeping the histories of the world close at heart, you can draw from them and understand that you are not so alone with the big questions—that others have grappled with them and lived their way to certain insights. In the same way, there’s something more banned book lists can tell us than might be obvious.

Rather than dismissing the reasons those books were initially banned as ridiculous and antiquated, what if we looked at the legacy of banning in context of today? What if we saw Banned Books Week as another chance to lean into and explore all the ways we experience discomfort, especially when that unease stems from unfamiliar realities and ideas? I wonder if the lessons book banning has to show us are less about funny-in-hindsight overreactions by archaic people who are nothing like us, and more about the ways those uneasy reactions are still part of the fabric of the world. And perhaps in order to fight that type of response to distress — the instinct to shut down, turn away, close the conversation — means first acknowledging that societally we can still see part of our ourselves reflected back through the book challengers.

Banned Books Week can be a celebration of curiosity and of courageous intellect, as well as a chance, as Neil Gaiman put it, “to understand that truth is not in what happens but in what it tells us about who we are.” He goes on to say that part of allowing freedom of reading is also allowing freedom of thought and of language, that when when we allow both to live, we allow ourselves to live:

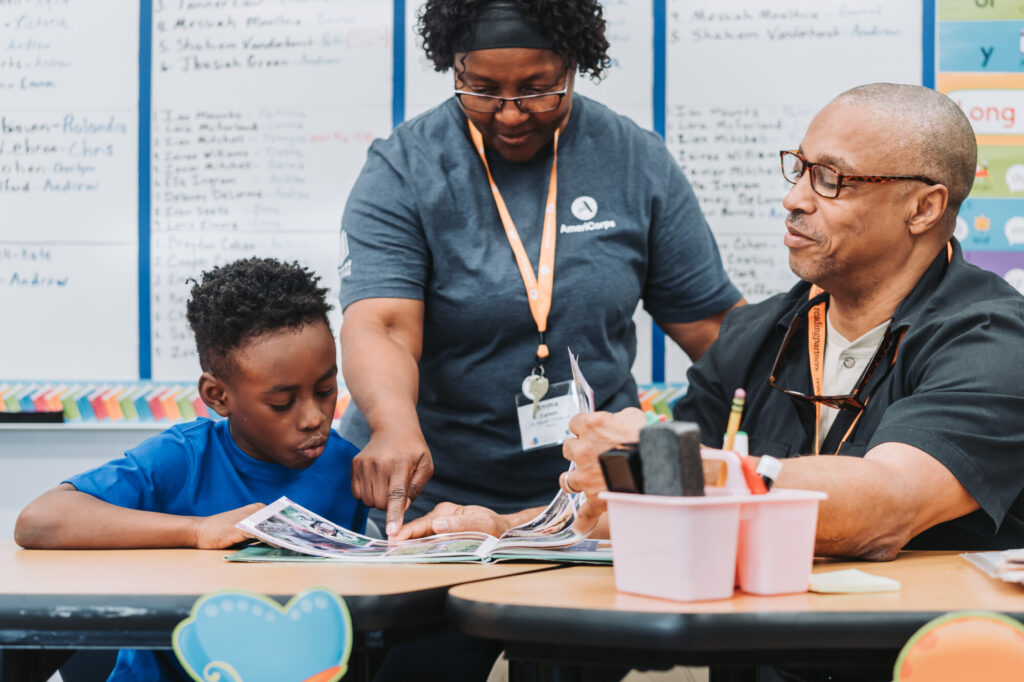

“We have an obligation to read aloud to our children. To read them things they enjoy. To read to them stories we are already tired of. To do the voices, to make it interesting, and not to stop reading to them just because they learn to read to themselves. We have an obligation to use reading-aloud time as bonding time, as time when no phones are being checked, when the distractions of the world are put aside. We have an obligation to use the language. To push ourselves: to find out what words mean and how to deploy them, to communicate clearly, to say what we mean. We must not attempt to freeze language, or to pretend it is a dead thing that must be revered, but we should use it as a living thing, that flows, that borrows words, that allows meanings and pronunciations to change with time.”