Access to high-quality literacy support can reduce incarceration rates

February 21, 2024

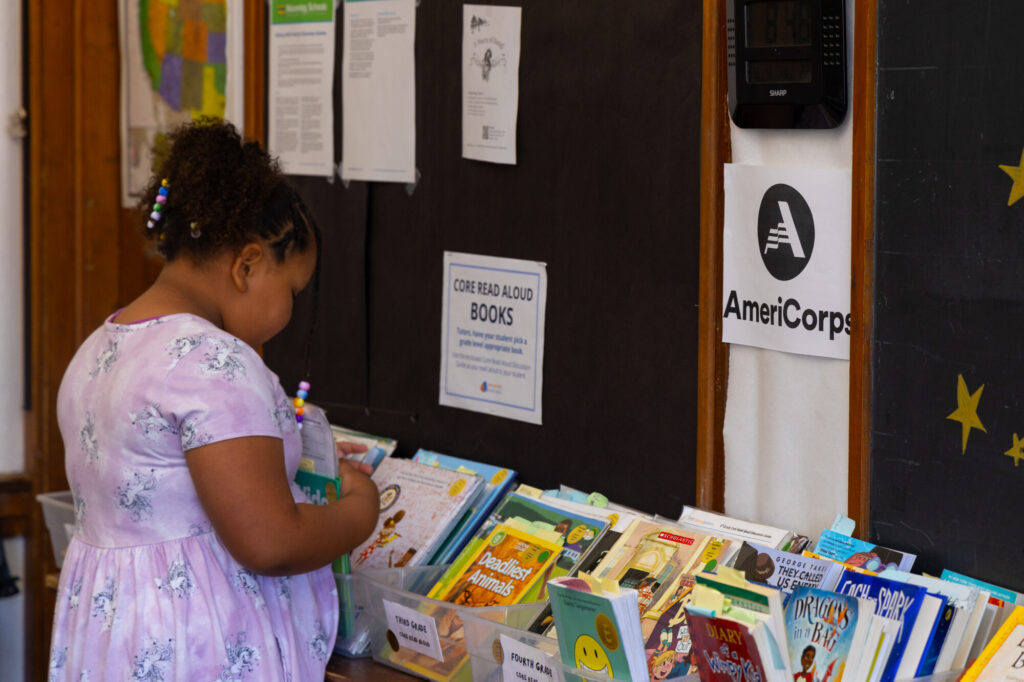

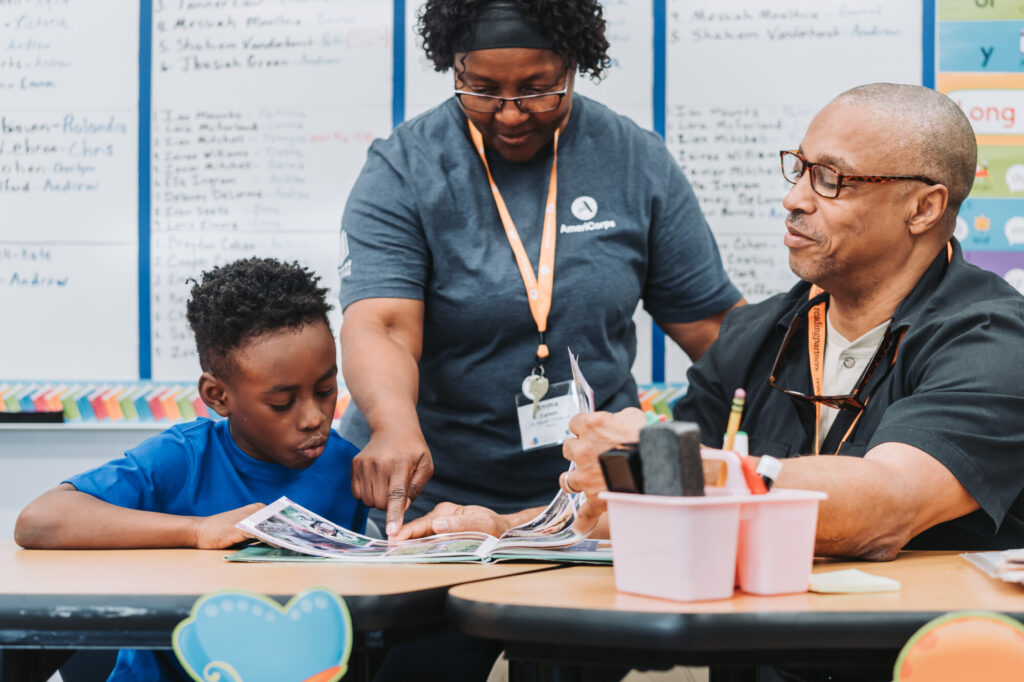

Volunteer coordinator, Reading Partners New York

In the 2022-23 academic school year, according to testing scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), only 33% of fourth grade students were reading at or above NAEP standards for proficient reading. Only 63% of fourth grade students performed at or above basic standards for reading. These numbers are catastrophically low. They are proof that in the United States, the strategies we are using to teach reading are not working. But even these numbers skew the truth of reading proficiency. For Black and brown children, the statistics are even lower with only 17% of Black and 21% of Hispanic students reading at or above NAEP proficient reading standards in 2022.

It is likely obvious to most that being able to read on grade level, and read proficiently is an important skill. Many parents would be understandably upset to learn that their child might not be reading at the same level as their classmates. But too often, conversations about literacy rates and reading proficiency in elementary school start and end with the importance of being able to read in school. We want our students to read on grade level so that they may succeed in the classroom, without considering what might happen to them outside of school should their reading level be an obstacle to academic success.

Reading proficiency in students as early as third and fourth grade is a major predictor of not just academic success through high school graduation, but of success outside of school. Specifically, we can find a high correlation between early reading proficiency and future imprisonment. In the United States, decades of systemic racism in policing and imprisonment policies has resulted in a prison population that is disproportionately Black and brown. As Michelle Alexander cites in her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, “the United States imprisons a larger percentage of its Black population than South Africa did at the height of apartheid,” (8). In this discussion, literacy rates among Black and brown students becomes paramount.

Reading proficiency in students as early as third and fourth grade is a major predictor of not just academic success through high school graduation, but of success outside of school. Specifically, we can find a high correlation between early reading proficiency and future imprisonment. In the United States, decades of systemic racism in policing and imprisonment policies has resulted in a prison population that is disproportionately Black and brown. As Michelle Alexander cites in her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, “the United States imprisons a larger percentage of its Black population than South Africa did at the height of apartheid,” (8). In this discussion, literacy rates among Black and brown students becomes paramount.

I find that literacy has only recently entered education conversations as an issue of social justice and civil rights. In examining the relationship between incarceration and elementary school reading, I hope to further solidify this link: prioritizing reading proficiency for elementary school students, especially Black and brown students, is one of the most important ways we can fight for social justice, equality, and equity for future generations.

Why is US literacy proficiency so low?

It is not an act of random chance that literacy rates in the United States are low. Many students are reading below grade level as a direct result of the literacy instruction many schools across the country have been using. There are two primary schools of thought surrounding literacy instruction: the whole language approach, and the structured literacy approach built on the science of reading.

The whole language approach focuses on teaching students entire words as one unit. Students are taught to skip over words with which they are unfamiliar, and use context clues and pictures to guess the correct word that fits in the sentence. The structured literacy approach focuses on phonics, teaching students the building blocks of reading that allow them to decode words they do not know using the sounds associated with each letter. This strategy has been proven time and again by scientific research to be the most effective way to build the neural pathways necessary for literacy growth in young students.

APMreports, a journalism and news outlet, produced a podcast called “Sold a Story” that not only detailed all the ways in which whole language learning has failed our students by ignoring the science behind reading and brain development, but which outlines a money-making machine that kept this style of teaching in schools for decades.

APMreports, a journalism and news outlet, produced a podcast called “Sold a Story” that not only detailed all the ways in which whole language learning has failed our students by ignoring the science behind reading and brain development, but which outlines a money-making machine that kept this style of teaching in schools for decades.

Only in the past five years have many states enforced a shift away from whole language learning and toward the science of reading. Unfortunately for many students, the damage has already been done. Our literacy instruction in schools across the country has been woefully inadequate for producing strong readers, and it shows in our literacy rates.

It is not that our students are incapable of learning to read, but that the tools and support they have been given are insufficient.

Low literacy rates, high dropout rates

To see the correlation between literacy rates and incarceration, we first need to understand the more immediate outcomes for students who are not reading on grade level in elementary school.

In a study done by the Annie E. Casey Foundation in 2012, researchers found that students who are not reading proficiently by third grade are four times more likely to drop out of school without a diploma than their peers who read proficiently. This jumps up to six times for students who are unable to master basic and foundational reading skills. Children who are not reading proficiently by third grade account for roughly 63% of students who fail to graduate high school according to this study.

In a study done by the Annie E. Casey Foundation in 2012, researchers found that students who are not reading proficiently by third grade are four times more likely to drop out of school without a diploma than their peers who read proficiently. This jumps up to six times for students who are unable to master basic and foundational reading skills. Children who are not reading proficiently by third grade account for roughly 63% of students who fail to graduate high school according to this study.

These rates are even worse for children in families from lower socio-economic backgrounds. The Annie E. Casey Foundation report points to a phenomenon called “double jeopardy” wherein children from lower socio-economic backgrounds are at a disadvantage both because of their economic status and their reading proficiency, compounding the effects to make them even less likely to succeed. While the likelihood of not graduating high school for students who are not reading proficiently is around 15%, the likelihood of not graduating high school for low-income students who are also not reading proficiently skyrockets to 35%.

This is also true for Black and brown students. As cited earlier, 17% of Black and 21% of Hispanic students in fourth grade tested at or above NAEP reading proficiency standards. In 2022, 28% of Hispanic and 20% of Black individuals were also considered to be part of low-income households.

The school-to-prison pipeline

In a study conducted in 2008 and 2009, researchers found that one in every ten male high school dropouts was incarcerated or in juvenile detention, and the rate of incarceration for high school dropouts compared to college graduates was almost 63 times higher. These numbers were even higher for young Black males, as nearly one in four young Black males were incarcerated or in detention.

For students who drop out, incarceration is often a result of environmental factors outside their control. For example, students who drop out are much less likely to find employment. In 2008, only 46% of the nation’s dropouts were employed. If you are unable to read with basic literacy skills by the time you are 17 or 18 years old, your ability to succeed in the classroom and workforce is severely diminished. You would be unable to fill out a job application, unable to search for postings online, unable to create a resume, and unable to fill out tax forms without assistance.

Ample research has been conducted to show the extent to which incarceration is an economic issue. A Prison Policy Initiative report showed that the median income for incarcerated people in 2014 was around $19,000. Students who drop out of high school and are able to hold a stable and legal job are often relegated to careers that yield incomes falling on the lowest end of income distribution in this country. That is through no fault of the student, but is rather a result of systemic issues in American literacy instruction. Incarceration becomes a much more likely outcome in a country without safety nets for those who are unable to navigate the employment market.

Ample research has been conducted to show the extent to which incarceration is an economic issue. A Prison Policy Initiative report showed that the median income for incarcerated people in 2014 was around $19,000. Students who drop out of high school and are able to hold a stable and legal job are often relegated to careers that yield incomes falling on the lowest end of income distribution in this country. That is through no fault of the student, but is rather a result of systemic issues in American literacy instruction. Incarceration becomes a much more likely outcome in a country without safety nets for those who are unable to navigate the employment market.

The connection between literacy, dropout rates, and incarceration is one that has been made before. There is a myth that prisons use 3rd grade literacy test scores in order to determine the number of beds they need for the year. While untrue, it is not far fetched when analyzing the numbers. If students who are reading below grade level or have below-basic skills by third and fourth grade are more likely to dropout of high school, and high school dropouts are more likely to be incarcerated, then it stands to reason that students who are reading below grade level are at risk of entering a pipeline that takes them from elementary school to prison. Grade-level reading becomes an important predictor of future incarceration not because students who drop out are more inclined toward crime, but because as a society, we lack the basic resources to help and support high school dropouts without basic reading skills. When adequate support does not exist for students who get left behind by a system that has been failing them in reading for decades, we doom many students to this school to prison pipeline.

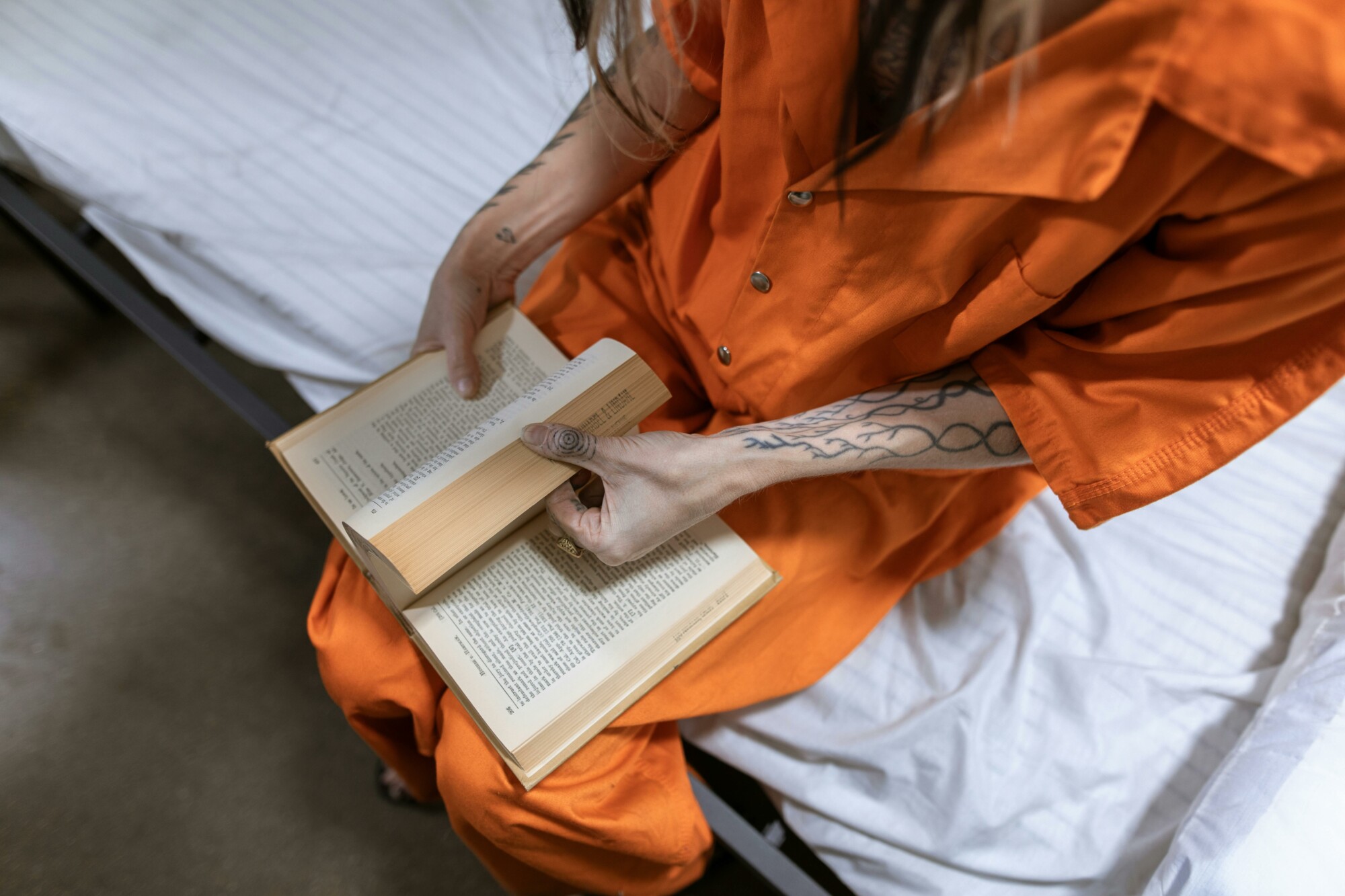

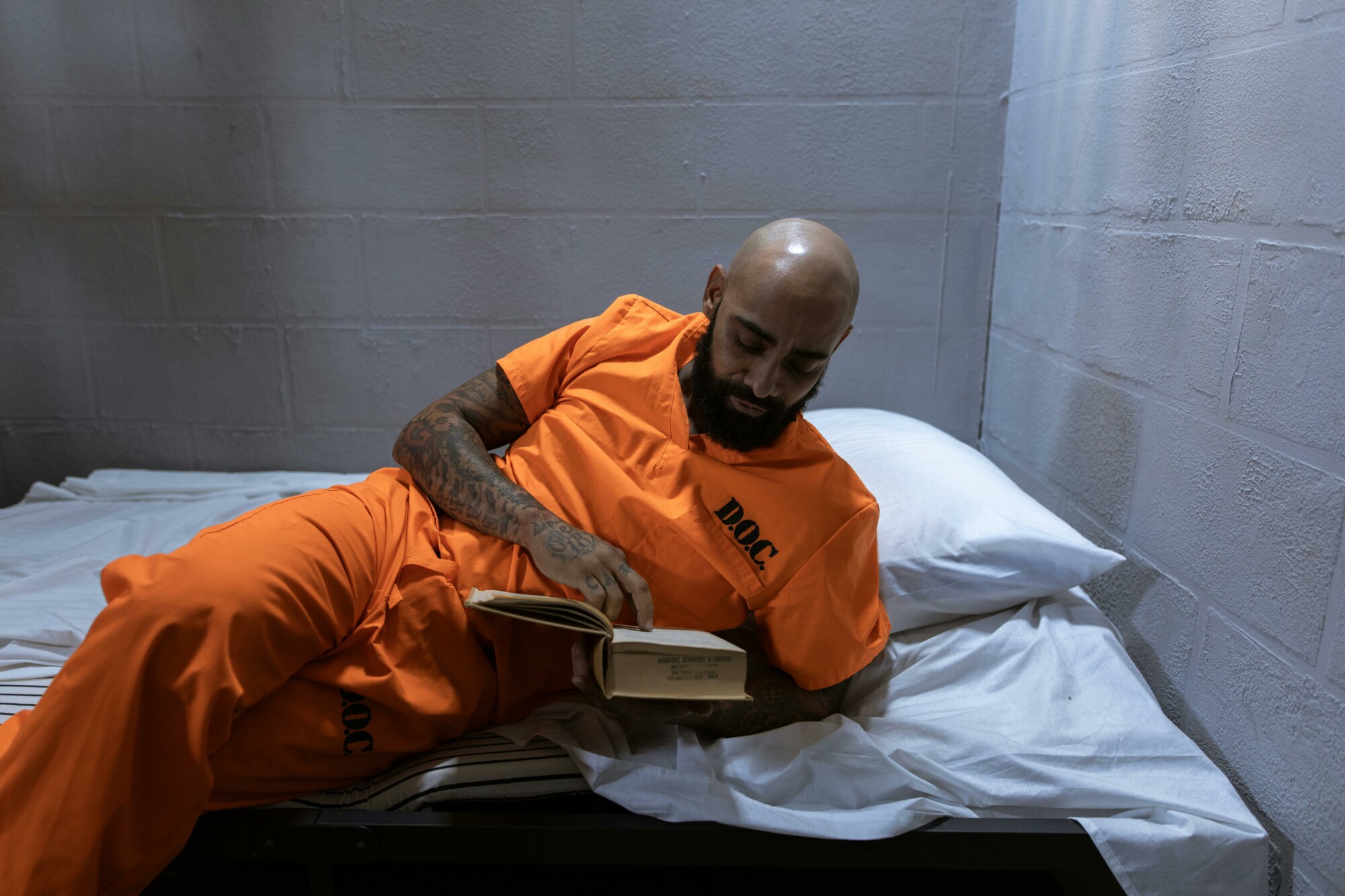

Reading proficiency and recidivism

In 2003, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) conducted a survey of 1,200 people incarcerated in state and federal prison and 18,000 non-imprisoned Americans with the aim of assessing literacy skills in both populations. In this survey, the percentage of incarcerated adults reading “below basic” on prose, document, and quantitative literacy was substantially higher in each category compared to non-imprisoned individuals. Notably, 78% of incarcerated individuals read below basic for quantitative literacy compared to 54% of non-imprisoned adults, a 24% gap in reading proficiency for those imprisoned. For prose and document literacy, 13% and 16% more incarcerated people had below basic reading skills for each category respectively.

Prison recidivism is not a perfect measure of success after incarceration as it is often subject to discrepancies with arrests and police reports; however, for this analysis, connecting literacy rates to prison recidivism helps clarify the picture. In 2018, the United States Bureau of Justice conducted a survey that found that 68% of people released from prison in 2005 returned to prison within three years. In a nine-year follow-up from this study, these numbers are even more devastating. After less than a decade, 83% of released prisoners were re-arrested.

What is interesting about these numbers is that many prisons offer basic literacy courses for those reading below a sixth grade level, and some states, like Oregon, even mandate that incarcerated persons be enrolled in these programs. Yet literacy rates are disproportionately low for incarcerated persons, and recidivism rates are just as bad. Based on this study in Oregon, it seems that even when states prioritize enrolling incarcerated persons who are reading below certain levels, many are not actually enrolled, and funding for these programs is consistently underprioritized.

What this means is that on paper, prisons and correctional facilities are able to state publicly a commitment to rehabilitating incarcerated persons after release. It means that those in power are able to skirt responsibility for a prison system that has created a cycle of imprisonment. Michelle Alexander points to the period of punishment after imprisonment, wherein formerly incarcerated persons are denied employment, housing, education, and public benefits purely as a result of their criminal record. For those with below basic literacy skills, that level of discrimination is, in many cases, an insurmountable obstacle that leads people back to prison, caught in a cycle of imprisonment and, as Alexander writes, “perpetual marginality,” (231).

Photo by RDNE Stock project on Pexels

Where do we go from here?

I have always been very passionate about advocating for an end to mass incarceration. It is full of oppressive forces and inequities, and it is built on racist and biased foundations.

Michelle Alexander described, better than I could, how people who enter the US prison system “enter a separate society…governed by a set of oppressive and discriminatory rules and laws…They become members of an undercaste…predominantly black and brown people who…are denied basic rights and privileges of American citizenship,” (232).

But ending our system of mass incarceration is a daunting task. It requires going to bat against powerful lobbyists, private prisons, police forces, and most importantly the state and federal government agencies that have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

Literacy intervention provides an avenue to address not just mass incarceration, but a host of other societal inequities at their source. Providing literacy intervention for children in elementary school and attempting to close the literacy gap will help more children read at or above grade level by the time they get to high school. It will result in fewer students dropping out before they graduate high school, and as a direct result, fewer students who are economically and socially marginalized and disadvantaged by their lack of reading skills.

There are always institutional barriers that make solving these kinds of problems difficult. Just because someone knows how to read proficiently does not mean they will have access to quality healthcare. It does not protect them from discrimination and bias in policing and legal justice. It does not ensure that they will be able to raise a family on often-insufficient minimum wage salaries. Teaching reading is not a catch-all solution for every socioeconomic issue we face.

And yet, addressing literacy as one of the roots of these societal problems raises the floor for our capacity to create change. If more children are graduating high school because they are reading proficiently, it becomes easier to imagine a world where we break cycles of mass incarceration and marginalization. If more students have access to literacy support in elementary school, we can build a society where reading is no longer a gap we are looking to close for marginalized communities, but a foundational skill on which to build, uplift, and support those students. Incarceration rates could plummet if children stay in school through graduation and, as a result, have access to a much wider and more robust job market. We will always be fighting against discrimination, bias, and systemic inequities that have long been baked into our society; but, when students are reading proficiently in elementary school, doors will open for them to succeed despite these persistent obstacles.

Banner image by RDNE Stock project on Pexels

Works Cited

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press, 2010.

Alper, Mariel, Matthew R. Durose, and Joshua Markman. “2018 Update on Prisoner Recidivism: A 9-Year Follow-up Period (2005-2014).” U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, May 2018.

Dillon, Sam. “Study Finds High Rate of Imprisonment Among Dropouts.” The New York Times, October 9, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/09/education/09dropout.html.

“Do Prisons Use Reading Scores to Predict Number of Beds Needed?” Reading Partners, October 7, 2013. https://staging.readingpartners.org/blog/do-prisons-use-third-grade-reading-scores-to-predict-the-number-of-prison-beds-theyll-need/.

Goldstein, Dana. “What to Know About the Science of Reading.” The New York Times, January 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/03/us/what-to-know-about-the-science-of-reading.html.

Greenberg, E., Dunleavy, E., and Kutner, M. (2007). Literacy Behind Bars: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy Prison Survey (NCES 2007-473). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Hernandez, Donald J. “Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation.” The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2012.

Hollingsworth, Heather. “Why More U.S. Schools Are Embracing a New ‘Science of Reading,’” PBS News Hour, April 20, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/why-more-u-s-schools-are-embracing-a-new-science-of-reading.

“NAEP Reading: National Achievement-Level Results.” Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading/nation/achievement/?grade=4.

“NAEP Reading: National Achievement-Level Results.” Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading/nation/achievement/?grade=4.

“Prison Literacy Connection | Office of Justice Programs.” Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/prison-literacy-connection.

Rabuy, Bernadette and Kopf, Daniel. “Prisons of Poverty: Uncovering the Pre-Incarceration Incomes of the Imprisoned.” The Prison Policy Initiative, July 9, 2015. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/income.html.

Shrider, Em. “Poverty Rate for the Black Population Fell Below Pre-Pandemic Levels.” US Census Bureau, September 12, 2023. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/09/black-poverty-rate.html.

“Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong.” Accessed January 30, 2024. https://features.apmreports.org/sold-a-story/.

Sum, Andrew, Ishwar Khatiwada, and Joseph McLaughlin. “The Consequences of Dropping out of High School: Joblessness and Jailing for High School Dropouts and the High Cost for Taxpayers.” Northeastern University, October 1, 2009.

Pate, Natalie. “The Path to Prison Is Often Paved by Illiteracy.” Salem Statesmen Journal, August 7, 2022. https://www.usareads.org/the-path-to-prison-is-often-paved-by-illiteracy/.

“The Science of Reading and Balanced Literacy | Part One: History and Context of The Reading Wars.” Reading Partners, June 21, 2023. https://staging.readingpartners.org/blog/the-science-of-reading-and-balanced-literacy-part-one-history-and-context-of-the-reading-wars/.