The science of reading and balanced literacy | Part Two: The balanced literacy backlash and shift to systematic phonics

June 29, 2023

Marketing and communications associate

For years, no one could agree on the right way to teach literacy skills. Some, mainly scientists and scholars, believed in a systematic phonics approach including strategies for decoding, or sounding out words based on their letters. Others, mainly educators who believed that they knew their students best and that researchers lacking in classroom experience had less relevance, sided with a whole language approach. They believed that all students needed was a literacy-rich environment and enough context clues to figure out a word.

In the past decade or two, the whole language, or balanced literacy approach, was the go-to method for teaching reading. But in the wake of the pandemic, when schools are acknowledging that their students’ reading scores haven’t been improving for years, we’re starting to see a pivot towards systematic phonics instruction.

This is the second blog of our three-part series on the debate between the two approaches, why there’s been a sudden shift to systematic phonics instruction, and how Reading Partners uses the science of reading to inform our curriculum. Click here to read the first blog for the history and context on the science of reading and balanced literacy.

Here, we cover the backlash against balanced literacy and why we’re seeing this recent shift toward systematic phonics instruction.

Why Johnny couldn’t read

The backlash against balanced literacy has come in waves. In the 1950s, when the whole language approach was popular, Rudolf Flesch was tutoring a sixth grader named Johnny. Johnny was being held back a grade because he couldn’t read.

When Flesch started tutoring him, he realized quickly that Johnny was not decoding the words on the page. It was not in his reading curriculum to learn how to sound out words. So, Flesch turned to phonics.

Once Johnny learned how to piece together the syllables of the words on the page, his reading skills took off. Why Johnny Can’t Read was published shortly after. The book pushed back on the whole language approach and blamed the American education system for not teaching children how to read through phonics. He was the one to introduce the American public to the idea that the “whole language approach” wasn’t teaching kids how to read; it was teaching them how to memorize words.

While Flesch’s ideas resonated with the parents of struggling readers, educators continued to believe that all students needed to learn to read was to be immersed in literacy-rich environments, and that they would naturally pick up on the meaning of words through repeated exposure. So, the whole language approach continued to dominate reading curriculums across the country.

Vibes-based literacy and how educators were ‘Sold a Story’

The second wave of backlash against the whole language approach came in 2000 when the National Reading Panel reported that systemic, explicit phonics instruction was one of the five pillars of effective reading instruction. Many believed the report would end The Reading Wars. But it didn’t.

As Emily Hanford, the creator of the podcast Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong says, “Whole language didn’t disappear; it just got repackaged as balanced literacy. And in balanced literacy, phonics is treated a bit like salt on a meal: a little here and there, but not too much, because it could be bad for you.”

Jessica Winter, a journalist for The New Yorker, refers to balanced literacy as “vibes-based literacy:” the idea that students in literacy-rich environments will find their interests in books and be motivated by exposure to what they enjoy. It’s based on Lucy Calkins’ balanced literacy model and her book, The Art of Teaching Reading, in which she acknowledges that children who are thriving as readers and writers by the end of first grade usually seem to “just know” how to read. Calkins, the founder of Columbia’s Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, trained thousands of teachers using this balanced literacy idea through her Units of Study curriculum.

In 2003, the NYC Schools Chancellor, Joel Klein, started requiring schools to use the Teacher’s College method. But at the time, Units of Study wasn’t actually a fully fleshed-out program. “In other words, Klein had signed up for a curriculum that didn’t yet exist,” Winter writes.

While teachers were ecstatic about the opportunity to use Lucy Calkins’ curriculum, there were plenty of others who weren’t pleased about the direction New York City schools were headed. In fact, Susan B. Neuman, the Assistant Secretary for Elementary and Secondary Education, under George W. Bush, went to New York to tell them not to use Units of Study. And three members of the National Reading Panel wrote an open letter to the school system, explaining that the curriculum was “‘woefully inadequate’ and unsupported by research.”

Units of Study dominated the New York School scene for a good five years. Because of its success, many other published curricula were modeled after Lucy Calkins’ ideas. So even when Klein realized that students’ reading scores weren’t improving and decided to officially phase out Units of Study, many New York City schools continued to use curricula grounded in the same practices.

In other schools around the country that had also invested a lot of time and money into Lucy Calkins and her curriculum, it proved to be hard to make the shift from balanced literacy to systematic phonics instruction. It would take something big, something unprecedented. Something like a global pandemic.

The catalyst for change and pivot to systematic phonics instruction

When Covid-19 shut down schools across the country, it not only halted, but reversed the academic progress students had made over the past couple of decades. The 2022 NAEP Reading Assessment found that reading scores among third graders dropped three points since 2019.

Not only were school districts and education experts dismayed by the learning loss caused by the pandemic, but parents now had a front-row seat to their child’s education. Zoom school brought the balanced literacy curriculum to many families’ living rooms, and parents were realizing why their children were behind in reading.

In the first episode of Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story podcast, she talks with a stay-at-home mom named Corinne. When Corinne’s six-year-old son Charlie started attending kindergarten on Zoom, she was able to listen in. And what she observed wasn’t at all what she expected.

“The reading instruction seemed kind of–odd to her,” Hanford reports. “These were things kids were supposed to do when they came to a word they didn’t know…look at the picture. Look at the first letter of the word. Think of a word that makes sense. Corinne wanted to tell Charlie to sound out the word. But handouts coming from school were telling her that wasn’t a good idea, that sounding out words should be a last resort.”

Charlie’s class was being taught how to read through the balanced literacy approach. But it wasn’t working, and Corinne could see that in a way she couldn’t have pre-pandemic.

Covid-19 threw a wrench in education. It paved the way for new technology in classrooms. It made clear the gaps in educational opportunities, and it allowed something new to emerge: change. Now, school districts are diving into the data and realizing that the way they’ve been teaching reading for decades is wrong. Parents are advocating for more and better phonics lessons, and getting involved in their child’s education in ways they hadn’t before.

Ten years ago, it was rare for a state to have policies that mentioned, let alone favored the science of reading. But in 2021, twenty states had passed or were considering measures related to the science of reading. And Mississippi is a prime example of what happens when early education curricula get infused with the science of reading: students’ literacy scores soar.

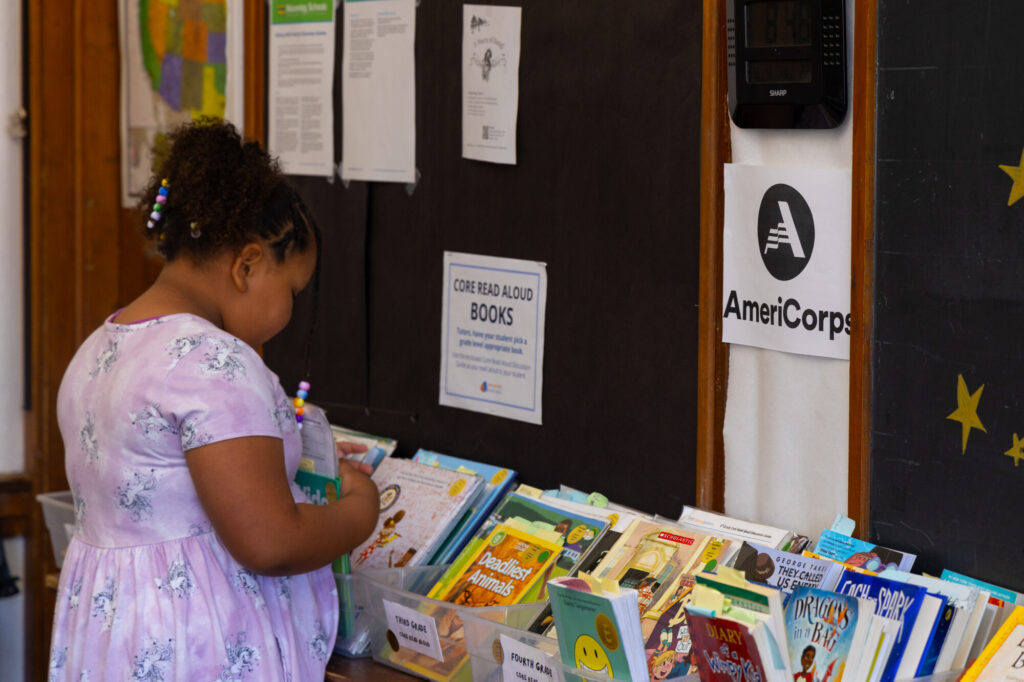

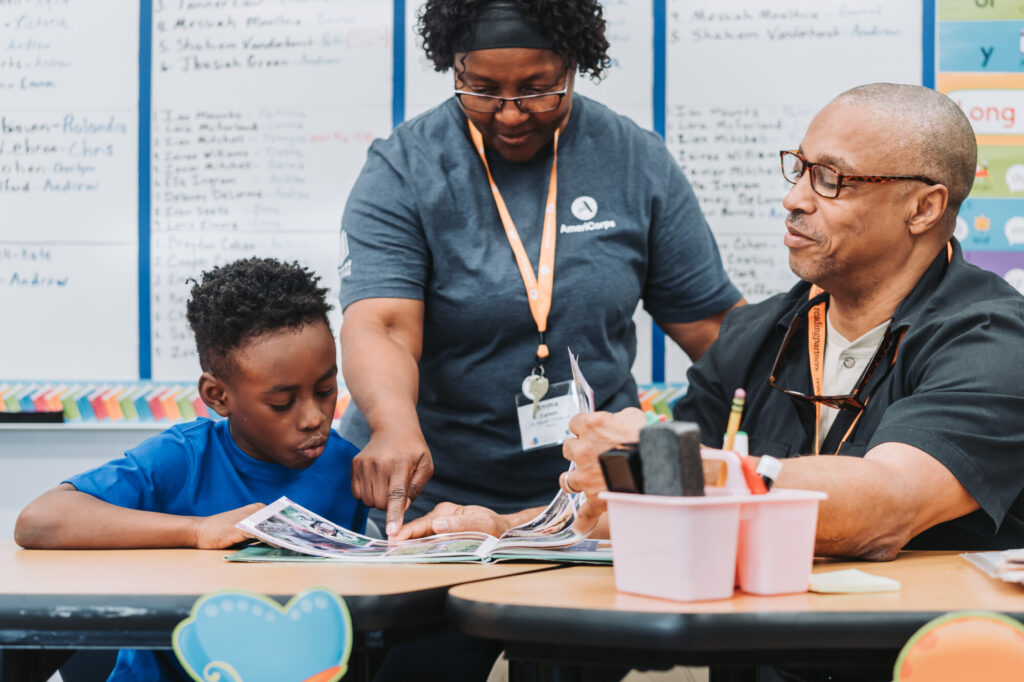

That’s why at Reading Partners, our curriculum is rooted in systematic phonics instruction. Our third and final blog in this series explores how our program draws on the science of reading to boost student literacy levels and instill in them a love of reading.

If you missed it, read the first blog in this series on what the science of reading is, how balanced literacy is different, and why educators and scientists can’t agree on one approach.